Dr. Clarence B. Jones on Race & Risk

Dr. Clarence B. Jones

Personal Adviser and Draft Writer

“I Have a Dream” speech for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

@cbjsenior

Jonathan Capehart

Journalist

The Washington Post

@CapehartJ

Dr. Clarence B. Jones, personal adviser and the draft writer of the iconic “I Have a Dream” speech for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., brought the house down at ComNet15 during his riveting conversation with The Washington Post‘s and MSNBC’s Jonathan Capehart.

Touching on the work that went into the March on Washington, the crafting of the “Dream” speech, race relations in America today, and what it takes to create social change, Dr. Jones offers inspiring insight into the civil rights movement and its applications to today’s world. Some of his advice? Foundations cannot be risk averse if they’re serious about change.

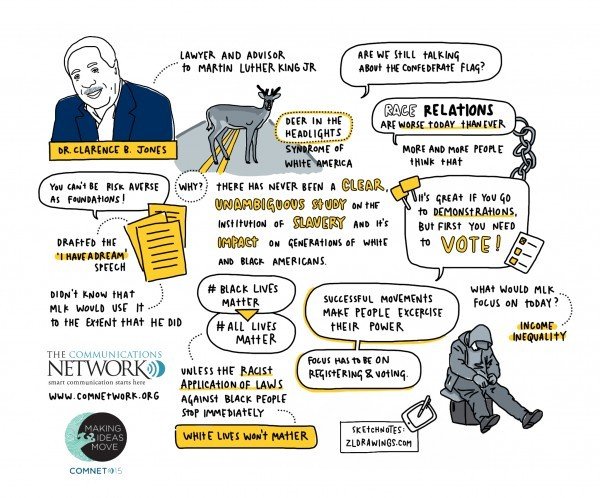

Watch the video, listen to the podcast of the keynote, read the transcript, or take a look at the illustrated notes.

Watch

Listen

Illustrated Notes by Zsofi Lang

Read

-

Joanne Krell: My name’s Joanne Krell, I work for the Kellogg Foundation. I lead communications there and I’m a member of the ComNet board and I am delighted to introduce this morning.

First, I want to tell you, recently a favorite uncle told me about a sales conference he worked on some time ago. It had a pretty typical motivational theme, something like Dare to Be Great; we’ve all gone to conferences that say that and, Dick Cavett gave the keynote.

And for those of you who don’t remember him or don’t know him, or maybe you all know him from his New York Times columns, he hosted a TV network talk show in the 70s and 80s featuring in-depth interviews and notable personalities, sort of the Jimmy Fallon of his day.

In his sales conference keynote, Cavett showed clips of three favorite interviews with Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, with Katharine Hepburn, and with Groucho Marx, and he gave some commentary about each. He started his premise by explaining that many interviews with famous people focus on what makes them like the rest of us.

But Cavett wanted to explore what made his subjects different. He wanted to understand the passion and the drive and insight behind their extraordinary work and that same question is relevant to our theme today.

The fact is if making ideas move was an established science, we’d have learned to move as journalism or marketing or public policy majors. We attend conferences like this because making ideas move is more than just science. There is art at work, and one key to understanding art is understanding the artist.

It’s fair to say that our keynote speaker this morning has married art and science to make ideas move on a mythic scale. So effectively, in fact, that he’s influenced generations and the course of the nation. As the former counsel and draft speech writer and personal friend of Dr. Martin Luther King, Clarence B. Jones played a key role in planning the 1963 March on Washington and he had a guiding hand in developing Dr. King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.

More recently, he’s continued to make ideas move through his books including “What Would Martin Say?” and “Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation,” and through his on-going work as the University of San Francisco’s inaugural Diversity Scholar Visiting Professor in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Clarence Jones will be interviewed this morning by Jonathan Capehart, a star who makes ideas move in his own right. He served as a policy advisor to former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg. With the New York Daily News editorial board he was awarded the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing, and he’s currently a Washington Post columnist, a member of The Post editorial board, and a frequent contributor to MSNBC.

Jonathan makes ideas move because he calls things as he sees them and he has the trophies, or depending on your perspective, the scars to prove it. In fact, if you see him at the break, you should ask him about his recent correspondence with Donald Trump.

In the meantime, please join me in welcoming Dr. Clarence B. Jones and Jonathan Capehart.

Jonathan Capehart: I’m so glad you gave Dr. Jones that standing ovation.

Dr. Clarence B. Jones: For both of us.

No, no, no it’s for you. I’m going to say something to you that you said to me, earlier, just before you made me cry, don’t interrupt me.

I first met Dr. Clarence Jones in New York City when I was on the Daily News editorial board in the 1990s. He was and is a handsome, elegant, unassuming man, unassuming in the best possible way. So it wasn’t until I was reading “Parting the Waters,” Taylor Branch’s Pulitzer Prize-winning tome on the start of the civil rights movement right up until the March on Washington, that I learned who he was, who he is.

In those pages I learned that the man I’ve gotten to know was integral to the planning of the 1963 March on Washington and the drafting of the “I Have a Dream” speech. The intense preparations for both caused Dr. King and his family to move into Dr. Jones’s New York home a month before the event that changed the course of history. In those pages I learned that the man that I quietly admired was the person who smuggled Dr. Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” out of the prison earlier that year.

It was Dr. Jones, lawyer, counselor, and speechwriter to King, who walked out of Chase Bank in New York City with a suitcase stuffed with $100,000 in bail money to secure the release of Dr. King and as many other demonstrators as possible in Birmingham, a suitcase handed to him by Nelson and David Rockefeller in the bank’s vault on 5th Avenue.

I saw Dr. Jones at Canaan Baptist Church in Harlem not long after reading those pages, and what I forgot to mention was I was reading “Parting The Waters” a couple of years after meeting Dr. Jones.

I went up to Dr. Jones in Canaan Baptist Church and I said to him, “You’re that Clarence Jones?”

I mean, I said this with a mix of awe and incredulity because I had to learn about him in a book. He didn’t … he didn’t feel the need to tell me. The man to my right not only had a front row seat during one of the most consequential times in our nation’s history, he was and remains an active player. Ladies and gentlemen, Dr. Clarence B. Jones.

Thank you.

So, I’m a … how many of you knew who Dr. Jones was before today, before the various introductions? So less than half of you, and that’s why when I was asked if I could think of anybody who could moderate this discussion I said, “Me, let me do it. Please let me do it, please let me do it,” and I told Sean earlier I would have walked across the country to be able to do this.

So Dr. Jones, it’s been 52 years since the March on Washington, since the “I Have a Dream” speech, since “The Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

Mm-hm.

We’ve seen enormous progress in that time, President Obama being probably the … the biggest and best sort of manifestation of that. But we’ve also had Staten Island, Ferguson, Baltimore, Charleston, North Charleston, Cleveland.

Mm-hm.

How would you describe race relations today given those two things?

First of all thank you for that generous, nice introduction. As a generic statement before I directly respond to your question, we marched, we worked so hard 52 years ago in hopes that those today would not have to march. So clearly the fact that they do means not that we were completely unsuccessful, but we were not as successful as we would like to have been.

What’s happening today in our country is not only a reflection of some of the things which were not sufficiently addressed during that period of time, but also a reflection of what I refer to and I mentioned to you, is what I call the deer in the headlights syndrome on the part of white America, and this is regrettable.

I don’t want to take too much time, but I would like to give you a quick example if I might.

Is this the … the story?

Yes.

The AG story?

Yes.

Okay, buckle up.

In 1963 the New Yorker Magazine, published major excerpts from James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time.” It created a firestorm in the country’s literary circles. As a result of that, the Attorney General of the United States, then Robert Kennedy, invited James Baldwin down to Washington to have a meeting with him.

As a result of that meeting, the Attorney General asked if James would convene a meeting of opinion makers that the Attorney General would have an opportunity to meet to get a pulse of what was going on in America.

So a meeting was convened at which, James of course was there, Harry Belafonte, Lorraine Hansberry, the playwright, Rip Torn, a white actor, Dr. Kenneth Clark who was responsible for the doll tests, and the Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation, Lena Horne, someone from New Orleans, Louisiana by the name of Jerome Smith, and myself.

And it was a very heated, animated discussion. During a part of that discussion Lorraine Hansberry said to the Attorney General, “You know Mr. Attorney General, the person you should be listening to here is Jerome Smith.” He had just come back from the front lines in Louisiana.

So there was a discussion about how the Attorney General told all of us and particularly Jerome Smith how much they had been doing for civil rights and particularly, protecting civil rights workers. Jerome Smith, with tears streaming down his face, told the Attorney General, who was about five feet away from him, “Mr. Attorney General, you are full of shit.”

Okay? He was red faced, but as a reflection, he reacted like deer in the headlights, a deer in the headlights, and Jonathan, you’d have to be deaf, dumb, and blind not to acknowledge that there’s been major progress, but on this issue of race and race relations in America, regrettably, still a large part of America reacts like a deer in the headlights.

And why is that? Is it because we as a nation don’t want to have the conversation? Or maybe I should say, is it white Americans that don’t want to have the conversation?

No, I think it is because for a whole combination of reasons in our educational system that there’s never been a clear, unambiguous study of an examination of the institution of slavery and its concomitant doctrine of white supremacy and their subsequent impact on generations of white and black Americans.

For example, I mean, how can there really be a serious discussion about the confederate flag?

It doesn’t compute if you have studied and know anything about … we had a civil war. The confederate flag was the emblem, it was the symbol of the confederate states who prepared to go to war in order to ensure that the institution of slavery and this doctrine of white supremacy would remain a part of the United States. Six hundred thousand people, Americans, lost their lives in the Civil War.

And so I hear people say, “But the confederate flag is a symbol of the great sacrifice,” — hello?!?

I mean, okay? Slavery and the confederate flag, which it symbolized, was one of the major tarnished, stained institutions on the history of this county, and our inability to deal with this is part of the problem we’re facing today.

Well, let me ask you this — this is something we were talking about before. There was a poll that came out a couple of months ago, asking the American people what they thought of race relations, and in fact the number has gone up, meaning more Americans feel that race relations are worse than they’ve ever been, specifically since the election of President Obama, as if electing the nation’s first black president would erase racism.

But we’ll leave that conversation for another day. When I read, read the story, I took the glass half full view of this.

I would agree with that.

And that is talking about race and racism is uncomfortable, it’s messy, it makes people angry, it has all of these negative emotions. And so to me, the rise in the number of people saying that race relations are worse is a positive thing, because if you know that it exists, you can’t say that things are better, especially after Staten Island, Ferguson, Cleveland, Sandra Bland, the pool party in Texas, all of these things.

Am I wrong in having this interpretation? Am I being short-sighted in having this interpretation?

No, you’re not wrong, you’re not being short-sighted.

It’s a reality that is part of the media, part of our culture. That observation is very astute. By the way, let me just say that what we’re talking about here today, Sean and the people who are running this organization, you’ve been very gracious in permitting me to sit in some of your meetings and so forth.

So when I tell you this issue of race in America is the most critical issue, I know who I’m talking to by the way, you’re foundations here. So I’ve sat in some meetings and I’ve heard some things, like “What should foundations be doing, how should they manage their money and their programs,” and so forth.

I heard some phrases like…and I know the gentleman who said this, and I’m not downright criticizing him, he was just stating a fact. He used the concept of, sometimes we have to be concerned about being risk averse, you know. And then I heard other discussions about [whether] foundations’ management should be prepared to stand up for their core values.

So here we are in 2015, and here we are, Jonathan Capehart and I are having a discussion telling you that this is one of the critical issues in your time. So I hope you’re still going to talk to me after this.

Okay? But I want to tell you there’s no way in hell you can be risk averse in the management of your money if you’re serious about making a difference about race in America.

And you already know this because I heard in some of your discussions that if you are with the foundation, managing the foundation, or you’re advising the foundation about their communications, you have to be concerned about the core values on which the foundation was founded, and there was a part of that discussion which says, well, you have to be prepared to act and stand up for your core values.

Hey, the money you manage was made possible by provisions in the tax code, okay? The monies you manage, quite frankly, as I said, were to enable you to do things that will make a difference, and yes, there is climate change so I don’t want to sound like I’m being stupid here, but you know, there were major issues of the environment.

I was so impressed, and I think this young gentleman here was talking about the five states of water and so forth. I’m not saying, well, you know, race is the only matter. That’s not what I’m saying. Some of the issues you address are very critical, but I am saying that in terms of real time, of what’s like the sword of Damocles hanging over our country today, we have got to address this issue of race in America.

You know, one of the, goals of the “I Have a Dream” speech was to get the nation to see that its fellow citizens were not being treated equally, either morally or legally.

Right.

And so could you talk about the crafting of the “I Have a Dream” speech? Was the goal to, persuade? Was the goal to cajole? Was the goal to do both those things?

Well, Dr. King and his family stayed in my home for almost five weeks, before August 28th, and so I had a chance. It was essentially supposed to be a place for him to have a vacation. But in any event, prior to the March on Washington, two or three days and the day before, we had talked about what he might say, and he had made notes and I had made notes and so forth.

But a couple of days before, in fact the night before at the Willard Hotel, he was upstairs drafting a speech and I asked him to come down because there were a number of people who worked close with him like, God, I’m getting old now, um …

Walter Fauntroy, a labor leader from New York, and Ralph Abernathy, the professor from Morgan State, and some of them offered advice and said, “You know Martin, when these people come here tomorrow, they’re coming here to hear you preach, you know,” and others said, “No Martin, you know they’re not really coming here to preach, you know, they really want to come for leadership,” and so forth.

And so there was a lot of controversy, back and forth, and during the meeting I made some notes of their discussion. In the interest of time I’m just going to say I made some notes, but anyway the meeting ends.

Dr. King was one of the most brilliant, extraordinary people; it’s not that he couldn’t write anything without Clarence Jones, you know. Don’t come away thinking that, that’s not at all [true].

But he had, you know, a lot of things to attend to, so I drafted out on yellow sheets of paper what I thought he might consider using as the opening paragraphs of his speech, you know, if he liked it and so forth. But it was really like a tool that I wanted him to be able to know that whatever he’s struggling with upstairs and writing, that as a safety net he had … I don’t know how many paragraphs, but several paragraphs of opening the speech.

Now in those paragraphs, months earlier I just had an experience at the Chase Manhattan bank with Nelson Rockefeller, but what you didn’t tell them is that, you know, they gave me $100,000, but they also, as I was quick to run out of the bank to go down to Birmingham for the bail, they said, “Hold on Mr. Jones, you gotta go over and consult that man over there.”

That man over there said, “What’s your name?” I said my name. “What’s your middle initial?” “Clarence Benjamin Jones.” So he’s typing out something, I said, “What’s that?” He said, “That’s a promissory note.” I said, “I’m a lawyer, I know what’s a promissory note.”

It was a demand promissory note. For those of you who don’t know, promissory notes in general have a day certain, “I promise to pay on or before such and such a date.” A demand promissory note is payable on the demand of the creditor, okay?

So I’m signing a demand promissory note, but when I left, I was so upset about it. I go to a telephone because Harry Belafonte had made arrangements for this. I call Harry Belafonte on the phone. He said, “How did everything go?” I said, “Harry, I got the money but you didn’t tell me I’d have to sign a promissory note.” He said, “Better you than me.”

I said, “You got much more money than I have.” Anyway, in the drafting of the speech, I remembered that and so in a paragraph I said, “When we are going to assemble here at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial, a hundred years after the emancipation proclamation, we’d like the American people to come and say to the nation, ‘You gave us a promissory note, but it was a bad check. You gave us a check and that was returned for insufficient funds.’”

So I wrote, “We refuse to believe there’re not sufficient funds in the vaults of justice to honor this note,” okay? So I drafted all that.

So … the next day is the actual March on Washington, and I’m standing like 50 feet behind Dr. King and I’m listening after he gives his perfunctory remarks and he begins to speak. And I’m listening very carefully. I said, “Oh my gosh, he’s actually using what I suggested.”

So I said, “Yeah, that’s good, you trusted me and so forth.”

And so to make a long story short the first seven paragraphs of the “I Have a Dream” speech for [various] reasons, he didn’t change a sentence, didn’t change a period, anything, exactly as I drafted.

In fact Dr. Jones, I mean, if there are things that people remember about the “I Have A Dream” speech, it’s the front portion, the promissory note, the vision, and then it’s the end portion, the “I have a dream” portion, and if you read the news reports from the time, the speech in the middle was sort of criticized as being sort of slow and perfunctory and technical and then I believe it was Mahalia Jackson who yelled out to Dr. King, “Tell them about the dream Martin.”

Yeah. Most people don’t know…

That was all extemporaneous. That was all off script, and what happened is that after he got finished reading the paragraphs which I had written and some other paragraphs that he added, Mahalia Jackson, who had sang for him, sang for the March earlier, interrupted him and said, “Tell them about the dream Martin, tell them about the dream.”

And so I’m watching him because I’m standing behind him and I see him, he sort of looks in Mahalia’s direction, but when she yelled to him he took the written text, he moved it to the left side of the lectern, and he grabbed the lectern and looked out on all those people. I’m standing behind him now and I say to someone who was standing next to me, I don’t know who it was, what color they were, male or female, but I said, “These people out there, they don’t know it, but they’re about ready to go to church.”

Now, let me tell you something, Martin Luther King, awesome, awesome man. In terms of today’s technology, Dr. King could mentally, as he’s speaking, he could mentally cut and paste in real time.

Okay? So as he’s speaking, and if you knew the speeches, as he’s speaking he would insert material from other speeches that he gave at other times but it would be done so seamlessly. So he had used the “I Have a Dream” speech on June 21st in Detroit Michigan where there was a demonstration of 100,000 people. He had used that speech in Cobo Hall, but it didn’t get any kind of reaction like it got there because it was the context in which he had used it.

I mean come on.

So, given what you’ve said about Dr. King and technology, it’s a great segue into my final question before we throw it out to Q&A.

So the civil rights movement, the “I Have a Dream” speech, they both have been sort of the template that other subsequent movements have used. Those two are the model, but times have dramatically changed, especially with social media.

So I’m wondering — I would like to have your perspective on how today’s advocates, the folks in this room, can connect with the larger public to achieve their goals and specifically, are there fundamentals that must be observed, and nurtured no matter how much things change?

I mean, we’ve got Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, all these other things that allow people probably right now to live tweet what we’re saying, whereas back in 1963 it might take a few days for what happened here to get out to the larger public.

But that being said, are there still things that must be done no matter how fast technology changes?

The current Black Lives Matter movement, for example, a reflection of the police thing and so forth, the various movements which are occurring today, particularly in so far as they presumably want to make a material change in race relations and conditions in America, unless a constituent part of that movement consists of voter registration and voting, with all due respect, it doesn’t matter how many placards you have, it doesn’t matter.

If you’re carrying a placard as part of the Black Lives Matter movement and you’re not registered to vote and you haven’t voted, well, that’s a contradiction in my terms.

Why do I say that? Because power, it’s about power and in this system of government … by the way there may be a better system of government than there is here, I don’t know where it is, I mean, the United States is the greatest country in the world, I have no problem saying that. Power.

I had a private meeting with the director of the FBI. It was prompted because he gave a speech at Georgetown University that blew me away, so I picked up the phone and called him. Lo and behold …

James Comey’s speech.

Yeah. So he called me back and I came down to Washington and I had a private meeting with him, and we talked about the Black Lives Matter movement and so forth, and at the end of the day I said, “Yes, we have to deal with this question of the persistent doctrine of white supremacy among our law enforcement and everybody, but we came away from that both agreeing there’s only so much that law enforcement can do, there’s only so much that the FBI can do, there’s only so much …

What’s going to make a change? It’s not so much just, you know, talking and talking and speaking and marching. You’ve got to vote, because it’s about power. It’s about political power, and if there ever was a time for America to exercise political power …

I mean, can you believe we just had another tragedy of guns? Okay? We just had another tragedy. I mean, how long are we going to sit and permit this kind of thing to happen without the congress of the United States addressing it?

And the congress of the United States is not addressing it because they don’t feel that they have to, and they don’t feel that they have to because they’re not getting the heat, they’re not getting the pressure from people who have the power to make them vote. So, very important that we vote, my brother.

One more question before we go to the Q&A, one of the things about the Black Lives Matter movement is that they’re very proud of being from the people, grassroots. Sort of in a way like the Tea Party, they don’t want any recognized leader. Is that a mistake? Should there be a recognized leader of the Black Lives movement and some visible structure?

Well, let me just say this. It may not be a mistake for 2015. The fact that it was important to have a leader 52 years ago may not be the same kind of paradigm today. So I’m less concerned about whether there is a recognized leader. I’m not so concerned about that as I am to the extent that they have some kind of collective, “we’re all going to act together” kind of syndrome, kind of mantra. That’s okay.

I repeat, leader or no leader, unless they focus on registering and voting, I sound very critical but I have to speak. Hey, when you get to be 85 you can almost say anything you want.

I look at the Black Lives Matter young adults, and I said to some of them, “We marched in hopes that you wouldn’t have to march.” So I don’t want those people who might hear this to assume that I’m trying to preach to you. No, I respect what you’re doing. I have admiration and affection for what you’re doing, but I am offering some advice that is very pragmatic that I don’t believe can be ignored.

Movements that do not focus on the acquisition of power are movements only. You have to make a difference, you have to get the leaders in power to make a change, and in our system of government that’s registering to vote and voting. I’ve preached enough I guess, so I’m sorry.

Q&A

Teddy: Thank you, Dr. Jones for everything you’ve done. My name is Teddy and I’m originally from Boston, so I grew up during the segregation there and, as I tell friends, the south had nothing on Boston during this time. It was terrible but, my question is when you’re talking about voting and it being the most important thing, here we are in a time where all of these efforts are being made to prohibit voting again, which feels like a repeat, whether it’s North Carolina or Ohio, some of the legislative actions that are coming.

On that note, as foundations, should one of our highest priorities be voter education, voter registration, and trying to counteract some of the voting prohibitions that are coming around?

In the 1960s, all of your foundations, collectively, you have a precedent, there was something called the Field Foundation. The Field Foundation had worked on a program of underwriting efforts to register people to vote during the 1960s.

The principal benefactor of that was Stephen Courier, and I think he and his wife died in a plane crash in the Bahamas, but the Field Foundation was the original template of foundation resources being directed to voter education and registration, and that made a difference, it made a difference in the 1960s. So the answer to your question is yes, it’s important.

Now, I should also I’ve a little bit of a legacy of Dr. King really stuck in me, right? So, I believe if he were alive that he would listen to the lawyers and he would listen to the advice of people like me, but at the end of the day he’d say, “You know what Clarence,” we can’t tolerate this anymore.”

So I believe that he would say, say in North Carolina, he would call maybe for 250,000 people, I don’t know, to surround the North Carolina statehouse, maybe 500,000, to quietly surround the North Carolina statehouse and to make known to the people in North Carolina that no business, no business will be conducted in this statehouse until you rescind these laws. That’s what I believe he would do. Non-violent protest.

Now, it’s always perilous, and I always counsel other people to do what I just did, and I always try to say, “You’ve got to be very careful, don’t be so presumptuous to say what Martin Luther King would or would not say,” but I’m going to express that belief so that’s what I think you should do.

LaMonte: My name’s LaMonte Guillory, the Communications Director for the LOR Foundation. My question is regarding the Black Lives Matter movement and I’m curious, how do we transition to all lives matter.

I’m in an inter-racial marriage. My wife is white, my kids are bi-racial, and there’s a significant movement, and it’s very important that black lives matter, but when I’m having that conversation with my kids or people that are not black, how do we transition that movement to say all lives matter?

Thank you for that question. I will offer, before I give my answer, Senator Elizabeth Warren last week gave an extraordinary speech at the Kennedy Center in Boston in which she dealt exactly with this issue, so I recommend that you go online and read the text of that.

But in direct response to your question, I believe that the Black Lives Matter movement at this time and place is not intended to say that white lives don’t matter.

It’s not intended to say that white lives don’t matter. It’s intended to say that in the recent period of time we have looked at the application of law enforcement and it appears that there’s been unnecessary, repetitive use of lethal force against young African-American men and in some cases, African-American women.

So to elevate the importance of that circumstance, these young people want to remind America that black lives matter, and by the way, white people who care about white lives matter with respect to law enforcement and other circumstances should support the Black Lives Matter movement because unless, listen to me carefully, unless this unmistakably racist application of laws against young black men is stopped immediately, guess what? White lives won’t matter.

Jesse: Good morning, thanks for, being here. It’s such an honor to share this space with you. My name is Jesse Beason, Public Affairs Director at the Northwest Health Foundation. My question is, much of the data suggest that philanthropy over the course of past 50 years has actually underinvested in black-led and other communities of color, in particular when it comes to civic engagement, especially past any four-year election cycle.

Do you think that philanthropy has a responsibility to resource those organizations almost in a course correction about what they haven’t been doing over the past years, or do you think that black-led organizations or other organizations of color have to take it on their own and develop their own resources in order to tackle the issue that you addressed, which was, the acquisition of power? Thank you.

As I said earlier in my remarks, I cannot think of any more critical issue today. I refer to the deer in the headlights syndrome with respect to race in America.

At the risk of a little self-promotion, I teach a course at the University of San Francisco. It’s a 15-week lecture course from slavery to Obama and this course, this year for the first time, is being designed to go online so it can be made available to students other than those at the University of San Francisco, and one of our principal focuses in doing that is to make it available to historically black colleges. And it is being reconfigured so it might be useful to more schools than in the Francisco unified school district.

Those of you who were foolish enough to give me your cards, you are going to hear from me, and those of you who do not give me your cards, then give me your cards so I can show you what we’re doing on this issue.

But it’s important, it is … hey, remember I said earlier your foundations have core values? You want to be responsive to some of the issues today, you cannot sit on the sidelines. You have to find a way of creatively providing funds to those organizations that you can determine your own …

I am not suggesting that you suspend due diligence, I’m not suggesting that you suspend the traditional, you know, examination that you’re dealing with somebody credible instead of a scam, but what should be that determination? Hey, what are you holding the money for? What’s the money for?

Of course you need to apply these funds to enable what you just suggested we do.

Eric: Martin Luther King, if the shooter had missed that day, if he hadn’t gone out on the balcony that day and stayed inside the room and he had lived, what was the unfinished work? How would he have spent the rest of his life? You knew him and you’ve partly answered that question, but I’m trying to ask in a fresher way.

Well, had he lived, this January 15th he would have been 87. I’m fairly certain that he would have devoted his time to the question of poverty and income inequality. Clearly he would have been focusing on, you know, law enforcement, racist or unequal application of law enforcement. But I think his priority would have been income inequality and getting government and private institutions directed to address some of the critical issues.

Think about it, the richest country in the world. The richest country in the world and you mean to tell me that there’s a United States veteran sleeping on the sidewalks in San Diego or under the bridges in San Francisco because there was no housing for them, they have no food? There’s a disconnect. How is it possible? How is it possible that we can permit this to happen?

So you foundations can do such and such, you foundations, which collectively by the way, last year foundations gave $358 billion. That’s all the foundations in America, okay? And what you gave from that was 2% of our domestic national product, 2%.

I understand you’re having your conference in Detroit next year? Could not agree more that that is one of the best places you could hold your next year’s conference.

Because you know as well as I do you’re either part of the problem or part of the solution, okay? And holding your conference in Detroit next year indicates to me that you want to be part of the solution. So I want to commend you on that.

Chloe: My name is Chloe Looker, I work with the Environmental Defense Fund and I just want to say thank you for speaking with us today. It’s extremely inspiring to hear you.

I work with an environmental organization, and although sometimes the connections of racial justice and environmental issues are not super-clear, we also know that issues of pollution, and environmental justice, you know, disproportionally impact communities of color.

So I’m wondering if you have any insights about how big environmental organizations like the one I work with, can work with communities of color in a more authentic way to try and solve some of these issues.

I think your question is pregnant with the answer. I think it’s a challenge for, I don’t know what particular community, but I think the challenge for those organizations that are committed to environmental change is to look around in the community in which you serve geographically and to find out what credible community organizations within the African-American community, within the Hispanic community, what organizations that you believe, based upon what they are doing, seem to parallel what you are doing.

I think it’s to be very proactive and to try to find out who those organizations are and to find out whether or not what they seek to do is compatible with what you seek to do and try to find a way of funding them, try to find a way of helping them.

Jed: My name is Jed Walker from the Atkinson Foundation.

First of all, obviously thank you for being here and thank you for all the work that you’ve done. People like me wouldn’t be here without you.

Thank you so much.

Jed: So, that being said this is a conversation about a conference on communication, specifically, and in organizing around issues of police accountability and all of these sort of racially charged political issues, if I had a dollar for every time someone quoted Martin Luther King and told me that I wasn’t being very King-like in doing this kind of work, I would be able to solve the problem of veteran homelessness across the country.

So how do we take our message and make sure that it is not corrupted, and that people do not continue to misuse Dr. King’s words in a way that is disgraceful to his legacy?

What an extraordinary question, thank you for asking that question. I think it is a challenge. I know that some of you are direct managers of foundation assets and many or most of you also dealing with the communication with the outside world about what your foundations do.

Actually, you know, what you just said is really maybe the jugular vein. Let’s assume that a foundation and its board and its operating management, you don’t have to convince them that there assets that should be employed to do what they want.

What you may have to convince them and to show them is how they can effectively communicate their message of how they best want to do something, and this is a really a challenge.

There is a challenge to avoid you not being taken by charlatans and to enable you to feel very comfortable that where appropriate, yes, you can quote Martin Luther King Jr. or anyone else where appropriate to make the point that you want to make. I guess I’m giving you a non-answer, by simply saying, you know, it is a major issue.

What you have said in your question is a challenge, and I think that others in this room who may be similarly challenged as the person who asked that question, I think you really have to think about that because that is an issue. How do you effectively communicate and how do you communicate so that the kernel of what you say is accurate and sincere and doesn’t have the feel of inaccuracy, or at worst, hypocrisy?

Angelle: I’m Angelle Fouther with the Denver Foundation, and it’s great to have you here. Dr. Jones, earlier you mentioned that we need to put the heat on, or sort of force the hands of our elected officials.

To make change, I am just wondering, when I take a look at a lot of our elected officials, our congressional assembly, I’m most often just shaking my head wondering if they’re going to get anything done.

And, my question is, when you compare the political leaders that you worked with and your congressional leaders from the civil rights movements to those that we have in office today, what differences do you see, in terms of our challenges and our opportunities to make them or to work with them for a change?

Well, let’s just take the republican party, okay?

Jonathan: We only have seven minutes.

Where … where are the Senators Jacob Javits from New York or the Senators Case from New Jersey? Where are some of the leaders in the Republican Party who were very active in civil rights? I believe that the issue with civil rights is not a democratic issue, is not a republican issue, it’s an American issue.

It’s an issue of conscience, and I also I’m aware, so I don’t want anybody to say, “Well, you know, Mr. Jones ought to know better.” I’m not trying to counsel. By definition, the reason you’re able to get your 501c3 and so forth is that in most instances, you’re not going to engage in any political activity. I understand that and I’m not suggesting that you do that.

I am suggesting, however this: there is sufficient statutory room for you to use your resources to educate your community, educate the public about those issues and about the persons in their community who could make a difference without necessarily the foundation taking any particular stand that you’re opposed or against any particular political official, you see what I’m saying? But I think you really must take the resources to educate, you know.

These are the issues, these are the positions that people hold, and you’re not, by providing that information, suggesting to them that you should vote for A, not vote for B. That’s not what I’m suggesting. I’m really suggesting that knowledge can set you free.

Dan: Thank you Dr. Jones for being here. My name is Dan Oppenheimer, I work for the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health in Austin, Texas. I kind of want to ask you a favor.

I don’t have any money in my pocket.

Dan: My wife and I are involved in an effort in Austin to change the name of our kid’s elementary school which is Robert E. Lee Elementary, and I think it might actually make a difference in our effort to exercise power if you could, if you felt comfortable from the stage, saying something to that, because my perked ears up when you talked about the confederate flag.

So if you have anything to say about Robert E. Lee elementary school in Austin Texas…

What I’ve said, if Robert E. Lee, is the Robert E. Lee you’re talking about …

And if he was a general of the Confederate army …

Dan: That’s the one.

Is that the one? Well, I think that school and its trustees, they need to have a “come to Jesus” moment because they know, there’s no question about it, they know what Robert E. Lee and the Confederate flag stand for, and how dare a public school or any school bear the symbol of this flag, which was the flag of the institution of slavery? That’s what it was about.

I am sorry, there was no nice way of saying it other than saying it as it is.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, I like to quote him all the time, he said, “Everybody is entitled to their opinion, but you’re not entitled to your own set of facts,” okay?

What I have just said about the Confederate flag and slavery is not my opinion only, but is based on a set of demonstrable, empirical, historical facts. The flag of the Confederacy was the flag of the institution of slavery and adoption of white supremacy, period. And how dare someone want to defend the flying of that flag, aside from desecrating the 600,000 people who lost their lives? I mean, please, there is some element of decency and morality, all right?

I know why this flag in South Carolina was taken down, because the people in South Carolina in Charleston and that state, they were overwhelmed by something they never thought they’d ever have to deal with, and that is the sense of forgiveness and grace on the part of the survivors of the victims, okay?

In the face of the most horrific form of massacre the people, the black people in the church said, “We forgive you.” Not all, some people in the church said, “We don’t forgive you,” but the fact of the matter is it was so clear, it was so clear that anybody who doesn’t act like that in the name of or in commemoration of the Confederate flag is saying they want to bring back or they want to celebrate the institution of slavery and white supremacy, and hello, that war was fought and lost, okay? I mean, this is 2015, get over it.

Grace: Dr. Jones, it’s an honor to hear your thoughts this morning, good morning. My name is Grace Maseda, I’m Marketing and Communications Director for Helios Education Foundation.

Okay. Are you going to give me your card before you leave?

Grace: Count on it. While we have visually integrated schools, there is a significant achievement gap between minority students and their non-minority peers. This is perpetual, it cuts across geography.

I’d like to hear your thoughts on how we address that challenge. Because without equal education, a foundation which propels our students, white, black, gay, straight, wherever you come from, we are not equipping our future leaders, our society and our country, to move forward. I’d love your thoughts on that.

Yeah, again your question is pregnant with the answer. You’ve answered your own question in the question.

What I’m saying is that, clearly, clearly the way you have described the issue requires the most aggressive active application of resources to try to address that in your community and other communities. You’ve described accurately, objectively an issue and a problem. So the question is how do you effectively apply the resources to address it?

Jonathan: So we’re out of time, but in closing, in talking about the humility of Dr. Jones, so in 2008, Dr. Jones wrote this book, “What Would Martin Say?” and I didn’t read it until August when I went on vacation. I was looking for something to read on my vacation and this is before this even came up.

And so I pulled it off the shelf and I was like, “Oh yeah, let me … oh, Dr. Jones,” and I opened it up and I had forgotten that you had written an inscription.

To you?

And it says, “Dear Jonathan, you may remember me as an investment banking consultant. I watch and admire you often on TV. I hope you take the time to read my book. This is the first of two books, the other one is on the writing of the, ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. I’m working on the second now. Best wishes, Clarence Jones.”

When I pulled this off, I remembered “You may remember me.” What do you mean, “You may remember me”?

Of course I remember you, and that speaks to what I was talking about the humility of this great man, who has done and continues to do so many terrific things, a man who without the work he did 52 years ago, I certainly wouldn’t be sitting here, we certainly would not be sitting in the same room together. And for that, Dr. Clarence B. Jones, thank you.

Thank you very much. I am so proud of [Jonathan Capehart], so proud of him.

Sean [Gibbons], I want to thank you and the directors of The Communications Network for inviting me here to give me an opportunity to speak to all of you today.

There is an African proverb that says that if the surviving lions don’t tell their stories, the hunters will get all the credit.

And so I’m grateful that as a surviving lion, you’ve given me an opportunity to speak about one of the extraordinary members of our pride, for example Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and so I thank you from the bottom of my heart for inviting me, and even if I’m not officially invited probably if you let me know I’m going to come to your next conference.

You hear me talk to you, but you should also know the effect you’ve had on me. I was profoundly moved in some of the discussions that I had. I’ve been profoundly moved by people who’ve come up and talked to me and people have been so gracious and say, “Mr. Jones I’m looking forward to seeing you on Friday morning,” and so forth. I look at that person, and I see he must be about 30 years old or 35, they know who I am and so forth.

But anyway I want to personally thank you. I shared with Jonathan, you know, the President of the United States had me into the Oval Office and took a picture on February 4th next to the bust of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and there were several people in the room.

Then he invited other people in the room and he said to the people, “You know why I’ve invited Dr. Jones here today? It’s that without John Lewis,” and he mentioned a whole lot of other people, “I wouldn’t be in this Oval Office.” And so that meant a great deal to me, and it means a great deal to me that you’ve invited me here today, thank you.

Thank you for coming.